As Wall Street’s passion for sustainability began surging about five years ago, Andy King looked on with apprehension. Academics at Harvard University, the London Business School and other institutions were churning out research asserting that doing good for people and the planet was also good for company profits. The papers have been quoted in US Senate testimony, cited by regulators crafting corporate climate rules and invoked by Wall Street firms marketing funds valued at billions of dollars.

King, a professor of business strategy at Boston University, questioned the studies’ conclusions. In decades of analyzing whether companies could profitably reduce their harm to the environment, King had found the financial gains were often too small to affect the bottom line. Digging into the latest research, scrutinizing complex mathematical formulas and parsing tens of thousands of data points, he discovered what he says are flaws that skewed the results. “The evidence supporting ESG just wasn’t solid,” King says.

Other scholars are increasingly reaching similar conclusions, with researchers from Columbia University, the University of California at Berkeley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and beyond releasing studies that bolster King’s work. These academics, generally supportive of efforts to combat global warming, have sparked a debate over the so-called ESG programs—guided by environmental, social and governance considerations—adopted by many corporations.

The critiques come as ESG is increasingly targeted by Republicans who see the embrace of environmental and social causes as a threat to American capitalism. Politicians have launched probes into Wall Street’s climate efforts, introduced anti-ESG bills in the states and pressured firms to quit climate-finance groups. But many people involved in studies questioning the validity of ESG emphasize that their research doesn’t imply that corporations shouldn’t seek to reduce their carbon footprint. “Companies should be doing as much as they can to decarbonize,” says UC Berkeley professor Panos Patatoukas, who recently published a paper that buttresses King’s analysis.

King, who co-founded an academic group that researches corporate sustainability and who’s served on the board of a firm that helped pioneer ratings of companies’ green and social credentials, started examining the studies around 2020. He and Luca Berchicci, a professor at Erasmus University Rotterdam, analyzed “Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality” by Mozaffar Khan (a former University of Minnesota professor now at Causeway Capital Management), Harvard’s George Serafeim and Aaron Yoon at Northwestern University. The 2015 paper found that companies with strong ESG ratings had significantly outperformed those with low ratings. It’s been referenced by finance heavyweights such as BlackRock Inc. and Morgan Stanley and cited more than 400 times, putting it in the top 1% of economic and business papers published that year, according to academic research database Web of Science.

The answers to these intriguing questions are strange and troubling. We can find some of them in the work of consulting insider, Matthew Stewart, and his enlightening, but misleadingly-titled, book, The Management Myth (Norton, 2009).

In his book, Stewart tells how in 1969, when Michael Porter graduated from Harvard Business School and crossed the Charles River to get a doctorate in Harvard’s Department of Economics, he learned that “excess profits were real and persistent” in some companies and industries, because of barriers to competition. To the public-spirited economists, the excess profits of these comfortable low-competition situations were a problem to be solved.

Porter saw that what was a problem for the economists was, from a certain business perspective, a solution to be enthusiastically pursued. It was even a silver bullet. An El Dorado of unending above-average profits? That was exactly what executives were looking for—a veritable shortcut to fat city!

Why go through the hassle of actually designing and making better products and services, and offering steadily more value to customers and society, when the firm could simply position its business so that structural barriers ensured endless above-average profits?

Why not call this trick “the discipline of strategy”? Why not announce that a company occupying a position within a sector that is well protected by structural barriers would have a “sustainable competitive advantage”?

Why not proclaim that finding these El Dorados of unending excess profits would follow, as day follows night, by having highly paid strategy analysts doing large amounts of rigorous analysis? Which CEO would not want to know how to reliably generate endless excess profits? Why not set up consulting a firm that could satisfy that want?

King and Berchicci replicated the analysis, running the data through more than 400 statistical models and using artificial intelligence to check the results. In the vast majority of cases, there was no evidence linking a company’s ESG ratings and its stock performance, they wrote in a 2022 paper published in the Journal of Financial Reporting. “Their analysis is meaningless,” King says.

In February, researchers at UC Berkeley who’d also replicated the paper by Khan, Serafeim and Yoon published a paper in The Accounting Review finding little connection between high ESG ratings and superior stock performance. The report, by Patatoukas and others, said Khan et al. had gotten the causality wrong. Companies that are larger, older and more profitable can more easily rectify problems to improve their ESG scores and better trumpet their strengths to ratings providers. Moreover, it’s those characteristics that lead to stock outperformance, not the ESG scores, the team said.

Khan, Serafeim and Yoon say they welcome scrutiny but stand by their findings: “We are pleased that academics continue to research the link between sustainability and company performance, a line of inquiry our paper inspired,” they said in an e-mail.

At Columbia, academics working with accounting professor Shivaram Rajgopal—who gave congressional testimony defending the use of ESG factors in investments amid the Republican backlash last year—replicated research by Caroline Flammer on green bonds (debt issued by companies to fund projects such as renewable energy). Flammer, now also at Columbia, said in a 2021 paper that when companies issue green bonds, their stocks rise and their environmental performance improves. The study was among several cited by the US Securities and Exchange Commission to support new rules for corporate reports of greenhouse gas emissions that were approved on Mar. 6.

Rajgopal and his team said Flammer’s analysis is skewed because it mainly captures the stock performance of SolarCity, a solar panel business now owned by Tesla Inc.—which not only accounted for the bulk of green bonds issued in the period analyzed but also for most of the share-price increase. Excluding SolarCity, the researchers said the stock market reaction to companies selling green bonds was insignificant, and they have little impact on a company’s emissions output.

Their paper is under review by the journal Management Science. Flammer didn’t respond to emails and phone calls seeking comment.

King also looked at a 2014 study by Beiting Cheng at Harvard, Ioannis Ioannou at the London Business School and Serafeim, which posited that companies with better social responsibility performance enjoyed superior access to financing, including borrowing money and issuing shares. When King repeated their analysis, he found the researchers hadn’t measured access to finance but had instead examined proxies based on things such as a company’s size, age and cash flow. King’s analysis is under review at the Strategic Management Journal.

Ioannou says King’s critique should be approached with caution because it hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed. “Our decision to use various metrics in our analysis at the time fully aligns with common and best practices,” he wrote in an e-mail.

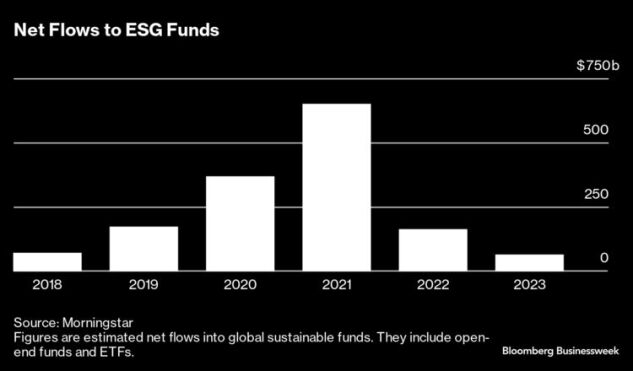

King bemoans the way ESG research has sparked a boom in sustainability funds, ratings and indexes, fueling a belief that wealthy people can save the planet while making money. “We ended up accepting supporting evidence uncritically,” he says. “When we make mistakes, we should be honest and open about it. What bothers me most is the squelching of critical voices.”

Professors who’ve closely examined his research, King says, have told him they agree with his conclusions but fear saying so publicly would hurt their careers. Even as they urge him to continue scrutinizing ESG studies, King concedes little will probably come of that as the papers he analyzes are unlikely to be retracted. But he insists he’ll keep going. “We need criticism and debate to ensure our evidence and conclusions are accurate,” he says. “My goal is to put pressure on the academics to fix this whole process.”